In March 2020, as the novel coronavirus swept across the globe, India—a nation of 1.4 billion people—stood on the precipice of catastrophe. Hospitals overflowed, oxygen supplies dwindled, and the death toll climbed with terrifying speed. The world’s second-most populous country was staring into the abyss of a public health crisis unlike any in its modern history.

But in a quiet lab in Hyderabad, a team of scientists led by a soft-spoken molecular biologist named Dr. Krishna Ella was already racing against time. Their mission: to develop India’s first indigenous COVID-19 vaccine. The odds were stacked against them. The virus was new. The science was uncertain. The pressure was immense.

And yet, from this crucible of chaos emerged a triumph that would rewrite India’s place in global biotechnology.

Bharat Biotech was no stranger to innovation. Founded in 1996 by Dr. Krishna Ella and his wife Suchitra, the company had already developed world-first vaccines for rotavirus, typhoid, and Zika. But it was still a David in a world of pharmaceutical Goliaths.

When COVID-19 struck, the global vaccine race was dominated by billion-dollar giants—Pfizer, Moderna, AstraZeneca. Bharat Biotech, with its modest resources, was not expected to compete.

“Everyone thought we were crazy,” Dr. Ella later recalled. “But we knew India needed a vaccine that was made in India, for Indians.”

In collaboration with the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) and the National Institute of Virology (NIV), Bharat Biotech began developing an inactivated virus vaccine—an old-school approach that had proven safe and effective for decades.

They called it Covaxin.

Unlike mRNA vaccines, Covaxin used a time-tested platform: whole-virion inactivated virus. The virus was grown in Vero cells, inactivated with beta-propiolactone, and combined with an adjuvant to boost immune response.

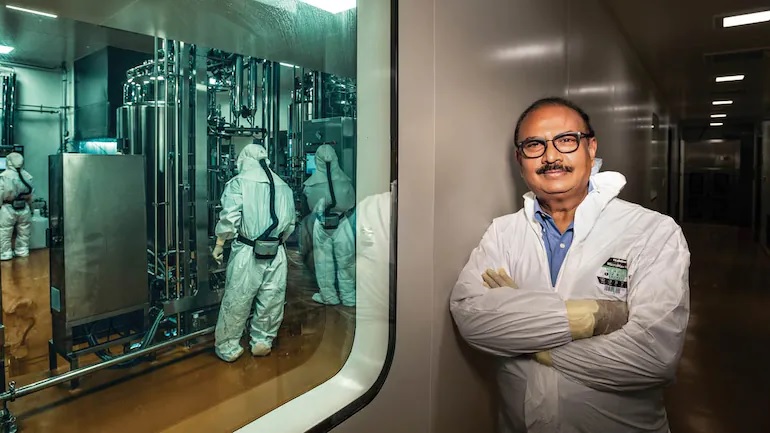

The process was painstaking. Every step had to be validated, every batch tested. But Bharat Biotech had a secret weapon: its BSL-3 (Bio-Safety Level 3) high-containment facility—one of the few in the world capable of handling live SARS-CoV-2.

By July 2020, Covaxin had entered Phase I and II trials. The results were promising: strong immune response, minimal side effects. But the real test lay ahead.

In November 2020, Bharat Biotech launched India’s largest-ever vaccine trial: 25,800 volunteers across 26 centers. The stakes were enormous. Public trust was fragile. Vaccine hesitancy was rampant.

Then came the backlash.

When Covaxin received emergency use authorization in January 2021—before Phase III data was fully published—critics pounced. Social media erupted. Headlines questioned its safety. Even some doctors hesitated to recommend it.

“We were vilified,” said Dr. Ella. “But we had the data. We just needed time.”

That time came in July 2021, when peer-reviewed results showed Covaxin had 77.8% efficacy against symptomatic COVID-19, 93.4% efficacy against severe disease and 63.6% efficacy against asymptomatic infection. The vaccine was safe, effective, and—crucially—stable at 2–8°C, making it ideal for India’s vast rural landscape.

India’s COVID-19 crisis was not just a medical emergency—it was a humanitarian disaster. The second wave in April 2021 brought scenes of mass cremations, oxygen shortages, and overwhelmed hospitals.

“It was the greatest emergency since Independence,” said former RBI Governor Raghuram Rajan.

Vaccination was the only way out. But global supply chains were broken. Rich nations hoarded doses. India, once the “pharmacy of the world,” found itself scrambling for vaccines.

Covaxin became a lifeline.

In November 2021, the World Health Organization granted Covaxin emergency use listing. It was a watershed moment: the first Indian-developed COVID-19 vaccine to be globally recognized.

By early 2022, Covaxin had been approved in 13 countries and was under review in dozens more. Bharat Biotech partnered with Ocugen to bring the vaccine to the U.S. and Canada, and with Precisa Medicamentos in Brazil.

“This is not just a vaccine,” said Dr. Ella. “It’s a symbol of India’s scientific sovereignty.”

Dr. Krishna Ella’s journey is the stuff of legend. Born in a farming family in Tamil Nadu, he studied agriculture, earned a PhD in molecular biology from the University of Wisconsin, and returned to India with a dream: to make affordable vaccines for the developing world.

He started Bharat Biotech in a rented building in Hyderabad’s Genome Valley. His first product—a hepatitis B vaccine—was the world’s first caesium-free formulation. Over the years, he built a portfolio of 19 vaccines, 145 patents, and a reputation for scientific rigor.

“He’s the vaccine wizard of India,” said Dr. Gagandeep Kang, virologist at CMC Vellore.

Covaxin’s success was not just Bharat Biotech’s—it was India’s.

It proved that Indian science could innovate, manufacture, and deliver at scale. It inspired a new generation of biotech entrepreneurs. And it challenged the global narrative that innovation only happens in the West.

Today, Bharat Biotech is working on:

- An intranasal COVID-19 vaccine (iNCOVACC)

- A low-cost malaria vaccine in partnership with GSK

- Vaccines for chikungunya, Zika, and more

“We’re not just making vaccines,” said Dr. Ella. “We’re making history.”

As the world continues to battle new variants and prepare for future pandemics, the story of Covaxin stands as a testament to resilience, ingenuity, and the power of science in the face of adversity.

It’s the story of a nation that refused to be a victim. Of scientists who worked around the clock. Of a company that dared to dream.

And of a vaccine that became a symbol of hope—not just for India, but for the world.

Related Reading

![]()