A Journey Through Ritual, Rhythm, and the Surreal Wisdom of Doing Nothing

In the hills of Mokokchung, Nagaland, where the forests breathe and the wind carries ancestral whispers, there exists a festival that defies the modern obsession with urgency. It is called Moatsu, and it celebrates something radical: rest.

Not rest as escape, but rest as ritual. Rest as resistance. Rest as a way of remembering who we are when we are not performing.

Moatsu is the Ao Naga tribe’s post-sowing festival—a communal pause after the labor of planting, where the village exhales together. It is not a spectacle for outsiders. It is a lived rhythm, a cultural heartbeat, a dream shared in daylight.

To experience Moatsu is to enter a world where time bends. The roads to Chuchuyimlang twist like riddles, and the landscape feels sentient—hornbills glide like omens, pine trees murmur secrets, and the hills seem to lean in, listening.

There is no itinerary. No countdown. The festival unfolds like a memory—fluid, nonlinear, generous. One moment, you’re sipping rice beer with elders who speak in parables; the next, you’re watching young men sprint across bamboo poles suspended over mud, their laughter echoing like thunder.

The surreal is not decoration—it is essence. A lore that tells about a monkey hired to sow rice plants bananas instead. A war dance becomes a mythic invocation. A forest flute leads you astray, only to guide you home through children who giggle like spirits.

Moatsu is not just a celebration. It is a cultural narrative for celebration of taking a break.

At the heart of Moatsu lies a philosophy of ritual repair. The Putu Menden, the village council, performs symbolic acts of mending—patching roofs, blessing wells, invoking ancestral spirits. These gestures are not quaint—they are profound. They echo the Japanese kintsugi, where broken pottery is repaired with gold. Here, broken homes are repaired with hope.

The rituals are not static—they evolve. They absorb the present while honoring the past. They are living archives of Ao identity, encoded in dance, drink, and storytelling.

And in this ritualized rest, something extraordinary happens: the community remembers itself. Not as a collection of individuals, but as a shared story.

In a world addicted to productivity, Moatsu offers a counter-narrative. What if rest were not a luxury, but a civic duty? What if festivals were not escapes, but recalibrations of collective rhythm?

Moatsu invites us to imagine a society where strategic laziness is institutionalized. Where rest is not passive, but active—an act of cultural preservation, emotional recalibration, and ecological attunement.

Could such a paradigm shift our understanding of time, labor, and meaning? Could it heal the fractures of hypermodern life?

Moatsu doesn’t answer these questions directly. It dances around them. It sings them. It drinks them slowly from bamboo cups.

On the final evening, the village gathers for Azü Joku, a hymn to the land, the ancestors, and the future. The melody rises like mist, wrapping around the hills. It is haunting, beautiful, and strangely familiar—like a song one has always known but never heard.

This is the emotional climax of Moatsu. Not a crescendo, but a communion. The villagers sing not for performance, but for remembrance. The song binds them—to each other, to the soil, to the stories that shaped them.

It is the heartbeat of Moatsu. And perhaps, the heartbeat of something larger.

Moatsu teaches us that rest is not emptiness—it is fullness. It is the space where stories ferment, where relationships deepen, where meaning ripens.

In the Ao Naga hills, rest is ritual. Joy is communal. Time is elastic. And doing nothing is not a failure—it is a form of wisdom.

As we navigate the noise of modernity, may we remember Moatsu. May we dare to pause. May we learn to listen to the hills that dream.

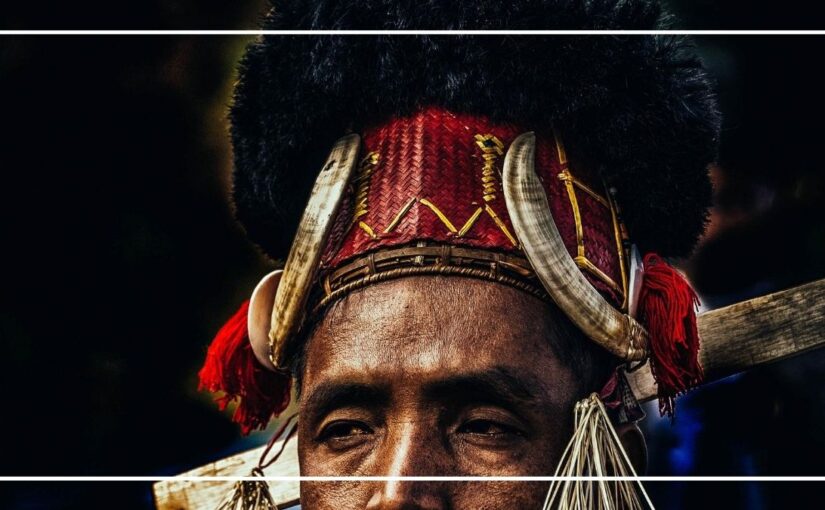

Acknowledgement : The credit of the feature image goes to Amitabh Sarma who runs a wonderful blog named Bearded Traveling Soul – please pay a visit.

![]()