“Sometimes, the first footprints are left not on home soil, but far across the ocean—inked in exile, penned in another tongue.”

In the early 18th century, long before Rabindranath Tagore redefined Bengali literature, before Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay stirred nationalist spirit with his prose, an obscure Bengali text appeared in a most unexpected place: Lisbon.

Not printed in Bengali script. Not in Calcutta. Not under British patronage. But in Latin script, under the watchful eye of Portuguese Jesuits, in the heart of Europe.

It was a book that quietly defied empires. A linguistic outlier. And for centuries, it disappeared from Bengali memory.

Until now.

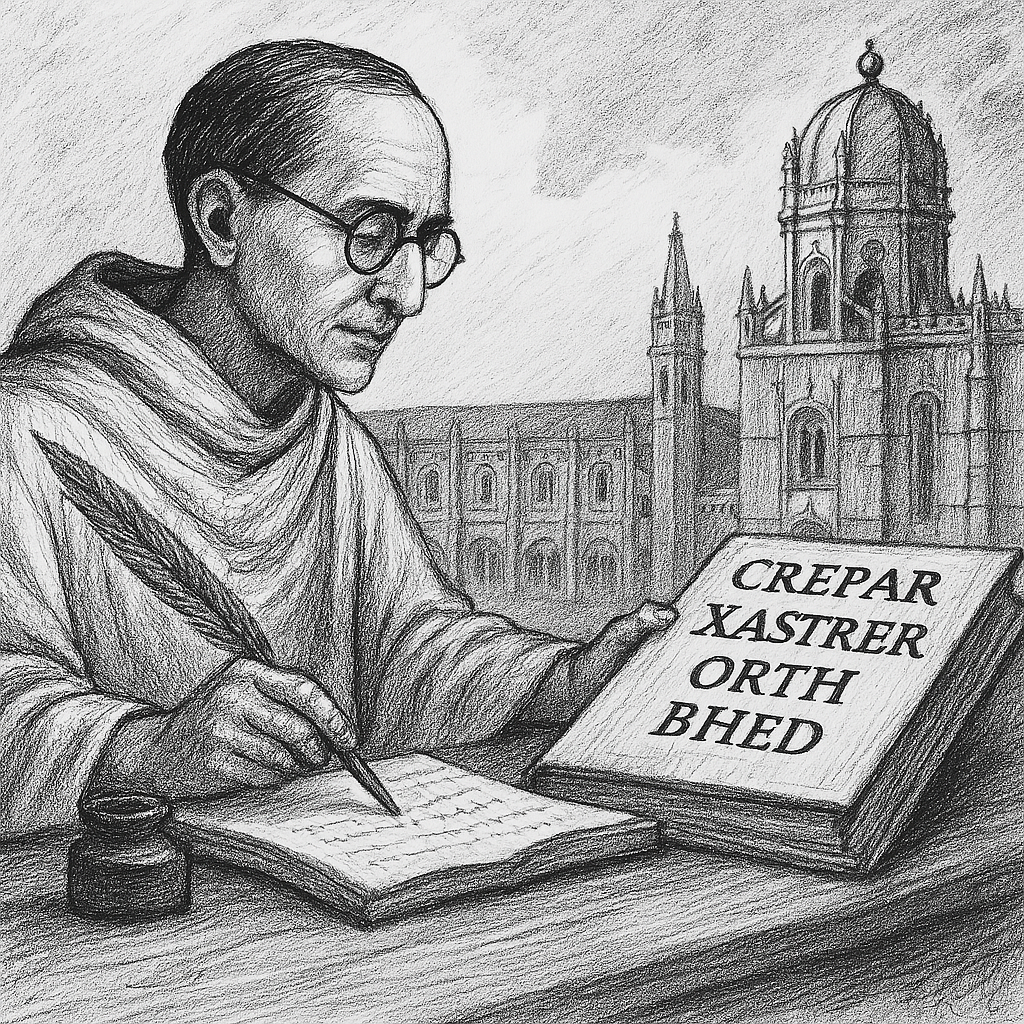

The year was 1743. At the royal presses in Lisbon, a slim volume was published under the title Crepar Xastrer Orth Bhed, which scholars now transliterate as Khristiya Shastra Artha Bhed—Exposition of Christian Scripture. The language? Bengali. The script? Latin. The author? An enigmatic figure known to us only through the imprint: Dom Antonio, a Bengali convert to Christianity, educated by Portuguese missionaries.

It was the first Bengali book known to be printed in the Latin script.

More than a century before the famed Bangalir Itihas or Iswarchandra Vidyasagar’s Barnaparichay, this book carried the phonetic flow of Bengali into the alien grooves of the Roman alphabet.

“The book challenges our entire chronology of Bengali print culture,” says Professor Sarmistha Dutta Gupta, a historian of early South Asian print literature. “It rewrites where—and how—Bengali modernity may have begun.”

To understand the book’s origins, we must follow the trade winds and missionary zeal of the 17th century Portuguese empire. Bengal, then part of the Mughal realm, had already seen Catholic missions active along the Hooghly river.

Jesuit records mention a small but growing population of Bengali Christians in Bandel and Hooghly, schooled in Latin grammar and European catechism. Among these converts, some were selected for priestly training abroad—spirited away to Goa, Rome, or Lisbon itself.

Dom Antonio may have been one such scholar—plucked from the delta, schooled by Portuguese missionaries, and initiated into the Latin liturgical world.

“These missionaries weren’t just translating faith,” notes Dr. Luís Filipe Barreto of the Universidade de Lisboa. “They were also transforming language—crafting tools to teach Christianity in native tongues using European scripts.”

The result was linguistic creolization: a hybrid Bengali, transliterated phonetically into Latin letters, retaining native idioms but often inflected with biblical metaphors and Iberian syntax.

The book might have remained a forgotten relic, were it not for the archival work of the Portuguese historian Father António da Silva Rego in the 1950s. Tucked within the Vatican’s Jesuit archives, Rego stumbled upon a reference to a “Christian doctrine in Bengalese,” printed in Lisbon in 1743.

Decades later, a single surviving copy was confirmed in the Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal. The pages were fragile, ink faded—but the voice was unmistakably Bengali.

Modern linguist Dr. Sudipta Mitra, who helped catalog the work in 2007, describes the moment he first held the book:

“It was as if I’d found the ghost of Bengali—not in Calcutta, but in colonial Lisbon. The words were ours, but the skin was foreign. A mirror held up backwards across the sea.”

The Latin-script Bengali was neither simplistic nor awkward—it followed the contours of native prosody. A sample line reads:

“Jishur prem o dhormo buchte hole, manusher ridoy paribartan korte hobe.”

(To understand the love and religion of Jesus, the human heart must be transformed.)

It was written to be read aloud, possibly by catechists or native priests. The text was both didactic and devotional. Alongside catechismal explanation were Bengali reinterpretations of parables, psalms, and moral teachings, suggesting the book was used to prepare missionaries and converts alike.

This Lisbon Bengali book predates any surviving Bengali printing in India. The first Bengali books printed in Bengal, such as Nathaniel B. Halhed’s Grammar of the Bengali Language (1778) and William Carey’s Padarthavidya (1801), came nearly six decades later.

This disrupts the established narrative that sees Bengali print culture beginning with British Orientalists and Serampore missionaries.

“It shows how colonial countercurrents were already flowing before the British script systematized Bengali,” argues Professor Gauri Viswanathan of Columbia University. “Portuguese missionaries were not only linguistic intermediaries—they created alternative modernities.”

The Lisbon book speaks to a different kind of hybridity—one shaped by global Catholic networks, not Protestant reformers. And its survival adds weight to the idea that Bengali literary modernity may have had multiple starting points.

Why Latin script?

Partly, practicality. The missionaries knew Latin, not Bengali script. But more importantly, script was power.

By converting Bengali to Latin script, the Jesuits created a new literacy—one separate from the Brahmanical and Islamic scribal traditions of Bengal. In their schools, new Christian converts could access knowledge outside the strict hierarchies of Hindu orthodoxy or Persian courtly language.

“It was a semiotic rebellion,” says Dr. Prabir Roy, a linguist at Jadavpur University. “Script becomes a marker of faith, class, and access.”

Over time, this script-linguistic divide would deepen. While the Bengal Renaissance reaffirmed the Bengali script as a cultural symbol, the Lisbon version would fade from collective memory—too hybrid, too colonial, too Christian.

No known copies of Crepar Xastrer Orth Bhed exist in South Asia today. Its story lives on in dusty catalogues and digital facsimiles in European libraries. And yet, its echoes can be felt even now—in questions of script politics, regional identity, and the global journeys of Indian languages.

For scholars like Mitra and Barreto, the Lisbon Bengali book is more than an artifact.

“It reminds us that language doesn’t always grow in straight lines,” Mitra says. “Sometimes it loops back, crosses oceans, gets rewritten—and still, it survives.”

The first Bengali book in Latin script was not a bestseller. It didn’t spark a revival or launch a literary movement. It was a candle lit in exile, by a people learning to speak their mother tongue through foreign letters, in the hope that faith could be carried across cultures.

We don’t know what happened to Dom Antonio. Perhaps he returned to Bengal, perhaps not. But his little book whispered something extraordinary:

That Bengali could be recast, rephrased, and reborn—not only under British eyes in Serampore, but under Portuguese steeples in faraway Lisbon.

And that, too, is part of the Bengali story.

![]()